How did a GM petunia end up in regular breeding programs?

"In 1987, a petunia was genetically modified", says Simons. "Several different breeding companies participated. At the time, they were very excited. However, 1987 isn't 2017. Now, no one wants to be linked with this method, or at least, they are quite reserved. For this reason these companies and institutions destroyed all the material."

Or did they? That's what the matter hinges on. "Orange petunias have been put on the market, so it cannot be excluded that the material used originated from the 1987 material. It is possible that someone - anywhere in the world - who was not aware of the GMO program became very excited about the orange petunia and started to breed using that GM material, assuming it hadn't been destroyed."

Speculating about the origin, Raimund Schnecking of German breeding and propagating company Volmary, has a similar theory. "Several breeders here in Germany think that the illegal GM variety originates from a trial conducted in 1990 by the Max Planck Institute in Cologne", says Schnecking. "At this Institute they probably did some transformations with plant genes, that were allowed on the condition that they would be destroyed afterwards. Maybe this wasn't done properly, which makes it a security question. However, we will see... investigations are still going on."

Unnatural color

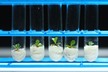

If transgenic plant material has been commercialized illegally and nobody else is aware of that, how can breeders assume that the material cannot be used? They can use each other's material to develop new varieties. However, it raises the question: what about the statement that orange isn't a natural color in petunias (as earlier stated by a researcher of Evira)?

In relation to this statement, it is interesting to note that just a few orange petunias tested by Dutch institute RIKILT, were found to have been genetically modified. On top of that, "the market is full of different 'unnatural' colors", says Richard Petri of Selecta One. This company is one of the breeders that had one of the GM varieties listed by Evira in their assortment. "The job of breeders is to create new colors within the same group of species. Look at Calibrachoa, Pelargonium… These colors and patterns do not occur in nature. Still they have been derived from conventional breeding methods, through crossing and selection."

Other varieties

Would it be possible that there are other GM plants or GM flowers on the market? "I have no idea", says Richard. "We had our petunia assortment tested by external certified labs, and the affected germplasm has been taken out and destroyed. Our petunia assortment is now 100 percent GMO free."

Richard also stresses that one should realize that trans-genetic methods are not very heavily applied in science on ornamental crops, as the practical execution is not that easy. "The Petunia is quite an 'easy' crop to modify genetically, other crops aren't. On top of that, it is not necessary to genetically modify a crop to create new colors or shapes. Our Night Sky for example has a new color pattern and has been bred with conventional breeding methods."

Simons adds that the fact that this material has been on the market for several years (and if his suspicion is correct, several decades), might be due to the ornamental industry itself. "This industry is more fragmented than the vegetable industry, enabling improperly obtained material to take on a life of its own, and the source is more difficult to trace."