“I’m not sure there was even an accepted term for what we did when I started, and many nurseries didn’t really know what to make of us. We weren’t growers and we weren’t a breeding company. So what were we then? There were a few of what we now call ‘independent breeder agents’, or plant licensing agencies, in the U.S. when we started in the early 2000s, but not many. In the time since I started, the services provided by companies like Dig have moved into the mainstream and there are quite a few options for representation. Nowadays, breeder agents are often the first option for many independent breeders looking to commercialize their new plant varieties. And patented plants seem to be a growing segment of most nurseries’ offerings as well,” says Sam McCoy, founder and owner of US-based Dig Plant Company, a patent and licensing agency for independent plant breeders.

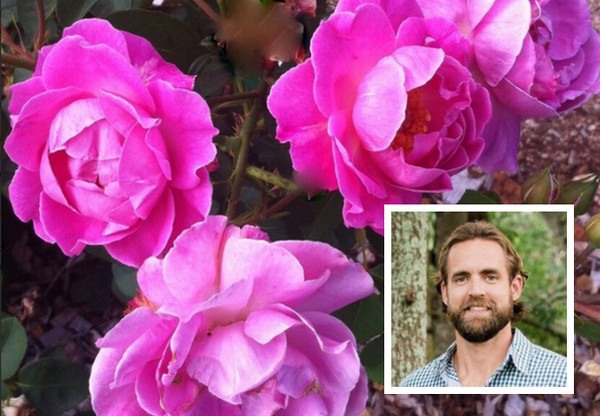

Sam McCoy, with the Brindabella First Lady roses in the background

An agency for independent breeders

Typically, an “independent breeder” will be a nurseryman or nurserywoman that has discovered a sport or made a seedling selection at their greenhouse or nursery. In other cases they are full-time breeders that are not affiliated with a grower or breeding company and, in rare instances, they are hobbyists. Whenever these breeders have a new plant that they want to commercialize, Dig and companies like Dig act as the conduit to market by protecting and subsequently licensing a breeder’s intellectual property to nurseries, greenhouses, and branded programs around the world.

Less than 25% patented

Introducing new plant varieties to the market has had a considerable evolution over the years. McCoy explains that new plant introductions were often handled very differently in the last century. “Oftentimes when a new plant was discovered or developed, the breeder wouldn’t even consider a patent. Many would assume, incorrectly, that it was too expensive or too difficult to obtain a patent, or that the act of protecting their intellectual property would be viewed negatively by other growers and colleagues. Instead, they would simply give their new plant a trade name that paid homage to their nursery, a family member, or themselves and then distribute it throughout their local or regional market, and maybe give the plant to some of their grower friends so that they could grow it too. In that way, the breeder would leave a legacy of sorts while also acting as a steward of the industry."

"The problem with that, however, is that the breeder would receive little to no compensation for having developed the plant. And if they did patent their new plant, a breeder would usually either keep it exclusively for their own nursery or enter into an exclusive licensing deal with one company. This strategy for distribution has worked for some breeders, but it also has the potential to greatly limit sales.” McCoy estimates that, back then, only around 25% of new plant introductions in the United States were patented, citing historical data from the United States Patent and Trademark Office which reveal a distinct increase in the number of annual plant patent filings beginning in the 1990s and continuing into the 2000s, until annual application filings peaked in 2013. McCoy notes that these data and observations are specific to asexually reproduced plants and do not include F1 hybrids and other seed grown crops, which is a space historically dominated by the larger breeding companies.

Awakening

Today, the attitude towards protecting and licensing new plants has changed and the practice is widely accepted by breeders and growers alike. One indicator of this change is the number of annual U.S. plant patent filings, which have more than doubled in the last 25 years. Many of these independent breeders now protecting their new plants will opt for professional representation to bring them to market, says McCoy. “There seems to have been an awakening over the years, and breeders now realize the value of working with an agent to navigate the market nuances; someone who knows where to place the plants, who understands appropriate royalty rates and license terms, and who understands how to best position and market the plant in order to maximize sales and royalties. And it’s not just breeders that have come around. More and more growers these days see the value in patented and branded plants, and they are willing to pay royalties and marketing fees for the benefits that come along with them. It’s an easier conversation to have with growers; they understand where we fit into the supply chain and appreciate what we have to offer.”

Changing with the times

“With the internet and all of the technology available today, it is much easier for breeders to have direct lines of communication with growers and potential licensees all over the world. And, in general, breeders are more informed on the mechanics of licensing. They have become more discerning of who they license their rights to and, I’m sure, wonder if it is even worth it to them to work with an agent at all. Breeder agents need to constantly reevaluate what we are offering so that we remain relevant to breeders”, says McCoy. Over the years, Dig Plant Company has modified, improved, and expanded their services in an effort to always offer a “value-add” relationship to the breeders they represent. For example, Dig has added additional services for breeders such as in-house patent prosecution and trademark consultation, which they offer as a stand-alone service or as part of our full-service representation. They are also in the process of building a 5-acre research and production facility to streamline the introduction process, improve their marketing capabilities, and to add more breeder services in the future.

Establishing the appropriate supply chain and distribution networks is critical, but equally important is creating awareness for a new plant in order to help drive demand. Most breeder agents provide marketing services as part of their representation. Though, the marketing services offered and the strategies employed will vary from one agent to the next. “We are always looking for more effective ways to market our portfolio of plants. Some things we try end up being quite effective while other attempts don’t work out. But we have to keep innovating if we are going to keep up with the times or, hopefully, get ahead of the curve”, says McCoy.

Parting thoughts

Of course, if a breeder weighs all options and concludes that working with an agent isn’t in their best interest then they can certainly introduce their new plant themselves. But McCoy offers a word of caution to breeders that are considering pro se representation. “Sometimes there’s this misconception that getting a plant licensed is the ultimate objective; that, once you’ve licensed a plant, the hard part is done. That couldn’t be further from the truth. The hard work has only just begun. First, how do you know that you have negotiated market-appropriate terms? And you have to remember that there are often significant differences between the various world markets. What applies in Europe doesn’t necessarily translate to the American market, for example. Royalty rates will likely be different, the market size for a particular species may be smaller or larger and you need to know how to manage your expectations, the supply chain could be unfamiliar to you, and so on. And, even if you feel like you’ve negotiated a good deal, there are a lot of other factors to consider. There is planting stock coordination required to initiate trials and production; there’s product support for growers; and don’t forget about marketing… that’s a big one. There’s also royalty reporting and collection management; monitoring for illegal propagation; cultivating licensee relationships to ensure that the new plant remains relevant to them (keep in mind that, these days, growers are being bombarded by new plants every year and it’s easy for additional new plants to take attention away from your new plant); some licensees will ultimately not work out and you’ll have to go on the search for new licensees. And the list goes on."

"Handling these functions in your home country may be doable for some, but not for everyone. And what about in foreign countries? Without a physical presence, it can be difficult to maintain and cultivate the relationships with licensees in order to maximize royalties. Breeder agents often have working relationships with counterparts in other countries and will work with these local agents to introduce new plants outside of their home markets.”

McCoy adds: “There are independent breeders that have invested the time and money to learn the ins and outs of new plant introduction and, as a result, have been successful with their plant introductions. But there are many more that have reached the conclusion that it is best to have professional representation. If you decide to work with a breeder agent, you may find that that the services of one company are a better fit than others. So breeders are encouraged to consult with several agents to make sure they find the right fit for them and their plants.”

For more information:

Dig Plant Company

Sam McCoy

[email protected]

www.digplantco.com