Homeowner gardens and farms and nurseries across the globe are fighting a tiny invader considered one of the world's most damaging pests.

The short-spined thrips, scientifically known as Thrips parvispinus, continues to attack a variety of ornamental plants like delicate gardenias, hibiscus and mandevillas to essential crops like peppers, beans and eggplants. This microscopic menace is leaving devastation in its wake for growers and home growers.

© UF/IFASShort-spined thrips

© UF/IFASShort-spined thrips

In a novel study, researchers at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) have unlocked the secrets of why this invasive insect has become a worldwide threat and how to control it.

The team of researchers has produced the most detailed portrait yet of the tiny, deadly invasive insect responsible for significant economic losses from the Americas to Asia. Their findings, published in the Journal of Economic Entomology, reveal the biological traits that have allowed this species to spread rapidly, especially across South Florida, and offer growers, regulators and scientists the first complete biological roadmap needed to design effective integrated pest management (IPM) programs tailored specifically to this species.

The results mark a pivotal milestone in the research by identifying the temperature ranges, feeding behaviors, reproduction strategies and soil-dependent life stages that allow the pest to flourish. The findings help explain the explosive spread in South Florida and offer the scientific groundwork needed to build effective IPM strategies for northern states, making the results relevant regardless of the location.

"We found that under South Florida spring conditions, the thrips thrive, so we can now be better prepared to implement preventive control methods to manage this pest," said Isamar Reyes-Arauz, lead author and a graduate student at UF/IFAS Tropical Research and Education Center (TREC) in Homestead.

© UF/IFASIsamar Reyes-Arauz

© UF/IFASIsamar Reyes-Arauz

The findings revealed that South Florida's climate is almost tailor-made for the short-spined thrips. At the region's average annual temperature of 27 degrees Celsius (80.6 degrees Fahrenheit), the insect completes its life cycle in less than 13 days and reaches its peak reproduction rate. This rapid development explains why growers across the region have seen populations surge in a short time.

Meanwhile, cold fronts slow the pest down because it can't survive long periods of extreme cold. Because South Florida rarely experiences sustained cold snaps, the study suggests winter offers natural relief. The insect easily tolerates short exposures to temperatures around 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit).

"The results suggest that the short-spined thrips is susceptible to prolonged cold temperatures below 5 degrees Celsius (41 degrees Fahrenheit), which is good news for northern states because it appears that the pest will not be able to survive outdoors during the winter," said Alexandra Revynthi, assistant professor of ornamental entomology and acarology at TREC. "However, under greenhouse conditions, we expect the thrips to be active year-round."

© UF/IFASAlexandra Revynthi

© UF/IFASAlexandra Revynthi

However, she noted that in South Florida, the warmer temperatures mean thrips might be active throughout the year.

The study also confirmed that females can produce male offspring without mating. Combined with a fast developmental cycle, this makes the species particularly adept at establishing new populations from only a few individuals.

"Knowledge of the reproductive mode is crucial because it tells us that from a single female, we can have the emergence of a new population," said Revynthi. "What's more, if that female is resistant to a pesticide, she can give birth to resistant offspring, creating a big challenge for the sustainable management of this pest."

For the first time, researchers documented that the pest pupates in soil, burying into an average depth of about 1 inch. This discovery opens new avenues for control, including soil-based biological control treatments such as beneficial nematodes, predatory mites or rove beetles.

"This is a turning point in the discovery," said Reyes-Arauz. "With this knowledge, we can now target the pest on the canopy and in the soil simultaneously, thus decreasing its population."

Researchers also discovered that this pest cannot survive long without live plants. That's good news for nurseries and greenhouses because simple sanitation steps, like removing unsold plants and clearing away plant debris, can make a big difference in controlling it. In the study, when the pest was given only alternatives such as pollen or honey water, it survived less than a day.

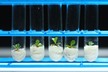

© UF/IFAS

© UF/IFAS

"Sanitation is a practical method that growers use to prepare the nursery or the greenhouse for the new crop," said Revynthi. "The results of this study suggest that if growers implement sanitation and leave the area without plants for a few days, they might be able to decrease the thrips population. Of course, this hypothesis remains to be tested."

Researchers are working to identify biological control agents that can help reduce this pest and to explore how these methods can be integrated with chemical control strategies.

For more information:

UF/IFAS

www.ifas.ufl.edu